Okay. Yeah. Sure.

Today Mercia S. Burger holds forth. She is an acclaimed writer and like my friend Louis Gaigher, she only reads literary books. She has a keen, unblinking eye and a way with words.

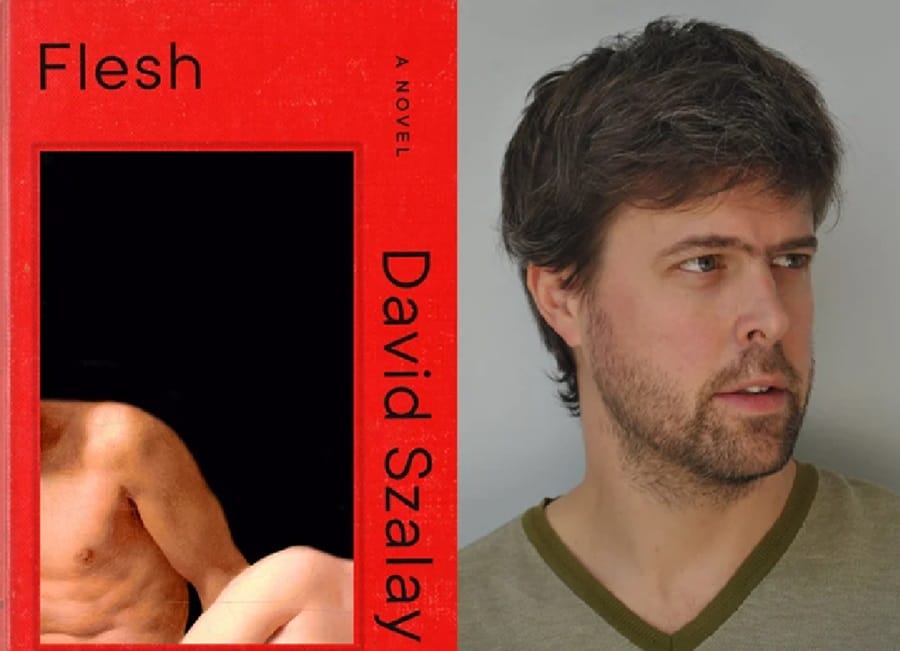

Just so we know what we’re talking about – the British-Hungarian writer David Szalay’s surname is pronounced Sol-loy. The “a” sounds like an “ô” and the “lay” like “loy.” What happens to the “z,” I have no idea.

All That Man Is, his collection of interwoven short stories that explore different experiences of masculinity, earned Szalay his first Booker Prize nomination in 2016. Gossip claims he only narrowly missed out on the award. Flesh (2025) is currently on the Booker longlist (the so-called “Booker Dozen”), but will hopefully – and probably – make it to the shortlist, which will be announced on September 23. The two books read well together as related and complementary texts, with Flesh serving as a literary echo of themes and characterizations Szalay had already begun to explore in All That Man Is.

The story

Flesh follows the life of István (his surname is never mentioned), who lives with his mother in an unnamed, quiet Hungarian village. The first chapter opens on a trot. István is fifteen when two incidents radically shape his coming-of-age and his experience of sexuality. A girl he wants to sleep with rejects him because he isn’t “sexy”:

“It’s horrible, to have that said to him, and about him, and yet he doesn’t know what to say or answer to it. It seems unanswerable.”

After that, he becomes involved with an older married woman who “grooms” him as a minor and draws him into a sexual relationship – one he accepts with resignation.

“Their encounters shift into a clandestine relationship that István hardly understands.”

The influence of these events on his formative years is never addressed directly, but you remember them, and you suspect.

From there, briefly, his life moves through a period in a juvenile detention home, compulsory military service and battlefield action, a few sessions with a psychologist, and eventually a shift from Budapest to London, where he lands an opportunistic job as chauffeur to a wealthy family.

The character

What I really want to get to is Szalay’s fascinating yet frustrating portrayal of István’s character. Forget the writing-school lessons about fully rounded characters with rich inner lives. Forget character arcs, reflection, emotional growth, and insight. István is written as a flat character, one-dimensional like a shadow, to the point of banality. This fits perfectly with Szalay’s minimalist style and recalls another rule-breaker and contemporary, Rachel Cusk, with her nameless, passive characters who listen more than they speak.

Repeated conversations between him and acquaintances, as well as with his later wife, Helen, are locked into reactions of “yeah” or “okay,” sometimes alternating with “yeah?” and “yeah okay.” Just to keep things interesting, there’s also “sure” and “sorry.” And on a sociable day, he might let loose with “What do you mean?” or “I don’t know.” So his life drifts on, driven by chance and by the decisions of others (especially women).

“He doesn’t know why he does what he does next. Something wells up in him,”

he tries at one point to analyse his feelings, and he reads self-help books like Playing to Win, but nothing changes. So much happens, yet it could just as well have been nothing.

His resigned passivity, bookmarked with one “okay” after another, his clumsy socializing, his deadening dullness, and his lack of opinions will surely frustrate and unsettle readers. That, of course, is exactly what Szalay had in mind.

An empty can

In an interview, Szalay mentions that he lived for a long time in both Budapest and London, and explains that he no longer really feels at home in either Hungary or England. A kind of insider-outsider, he describes the isolation experienced by someone living in a foreign city and country, speaking English with a heavy Hungarian accent – like his protagonist. Gradually, István becomes, almost imperceptibly, more complex.

Rather than reading him as a flat and one-dimensional character, one could also see him as an emotionally broken figure still wandering around in his teenage years. Read between the silences, in what is not said – what happened to his father? – and in what is never spoken of again.

The reader will have to endure a bit of discomfort and stick it out, but this guy is like an empty can with a pin inside. If you shake it hard enough, you do hear something after all.

Flesh by David Szalay is published by Scribner and costs R367 at bookdelivery.com.